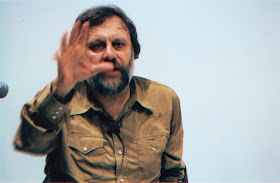

With this text we want to salute an absolutely arbitrary event in the life of one of the most important thinkers in today’s world. The event is his 70th birthday. Almost everyone will immediately recognize the thinker we want to celebrate, when we — as if this were philosophical Jeopardy — offer a number of highly subjective descriptions or “theses” of what makes him and his work worth such a eulogy:

1– He might be one of the very few thinkers in the history of philosophy, who at points makes it, even for his closest theoretico-political companions, almost impossible not to feel irritated or chagrined by some of the positions and claims he defends or (un-)strategic choices he has made. Depending on one’s temper, these sentiments are produced quickly or rather late. But one can rest assured that one will come to such a point.

2– This practical effect of his work is systematically reflected in his thinking. And this does not simply mean that he is a polemical figure, a figure of practico-theoretical polemos who simply enjoys the provocation (even though he sometimes seems to do so). Rather, this feature of his thought-practice is part and parcel of a refined elaboration of the concept of negativity and this also means, in more colloquial terms, of resistance. This is to say that his conceptualizations of negativity often provoke a negative relation to the conceptualized subject matter as its necessary ramification.

3– The preceding thesis comes with a further implication. For, maybe the most difficult aspect of an engagement with his work does not simply lie in straining to understand it. The problem is not so much how to make sense of it, but, rather, how one cannot but at points confront one’s own resistance to the practical consequence(s) and theoretical implications of what one is reading. This may happen when one is confronted, for example, with arguments that Gandhi was more violent than Hitler, that in a certain situation it would be politically more revelatory for Trump to win than for Clinton, that one has to repeat Lenin, perform an immanent criticism of #MeToo and more of the like. Such a position demands more than a simple defense and, clearly, more than a simple rejection. He dares (us) to think not something else, but otherwise.

4– One way in which working through resistance is reflected in his own thought is in his claim that great thinkers, like Plato, Descartes or Hegel, generate an almost endless series of resistances: some resist by declaring these thinkers to be only speaking nonsense anyhow, some by arguing that they are totalitarian or dangerous, others again by over-endorsing and over-identifying with their respective systems, so that resistance can appear in the form of acceptance, which complicates the picture (think, for example, of the conservative old Hegelians who after Hegel’s death dogmatically defended his system).

5– In this sense, the history of philosophy is nothing but a series of angry or excessively loving footnotes to Plato, Descartes and Hegel. We believe that the thinker, whose name you have certainly already guessed, can, in this precise sense, be compared to these (almost) eternal names of philosophy. One cannot not resist him and one cannot simply resist him.

6– This obviously raises the stakes. If we want to—and we most certainly do—remain faithful to the philosophical, political, artistic or psychoanalytic system of this thinker and to its consequences without endorsing a blind defense (even though it is sometimes needed) and without an idiosyncratically resisting rejection (even though it cannot be avoided sometimes), then the question arises: How to do this?

7– The French philosopher Alain Badiou has once argued that the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan is “our Hegel,” the word “our” referring to the generation that immediately succeeded Lacan. Different from the real Hegel—whom Badiou has criticized in a classically Marxist manner—, our own Hegel (i.e. Lacan) does present us with a new kind of problem. The old Hegelian dialectic, as Marx points out, has an idealist and a materialist side, and we must therefore sever the one from the other with great care to be able to put it to use for a materialist conception of dialectics. Things stand differently with “our Hegel”. For, strangely, he has been able to internally divide himself into two all by himself—he did not need a Marx to do so. Trivially put: he has divided himself into an early and a late Lacan, the latter radically turning the former (i.e. himself) from his head onto his feet. Lacan, our Hegel, thereby miraculously has been able to become his own successor, a Hegel who has become his own Marx. Now, we believe that the thinker in question is, once again, also “our Hegel”, yet one who strangely brought about a new Hegel that only became possible because of his way of reading Hegel (especially via Lacan, the Hegel of a former generation). So, we have before us a case where our Hegel produces a new and different Hegel. He creates himself as his own predecessor. Or, as “our Hegel” argues, One divides into one and itself.

8– The capacity to generate a transformation of the past (Hegel) is what can be taken as a defining feature of a great thinker. After him, even if you disagree with him on some points, the whole terrain of the debate is transformed. In this precise case, he is our Hegel, because after him Hegel (and Lacan), philosophy and psychoanalysis, will have forever been different.

9– The transformation in question has a determining impact on his rethinking of the foundations of dialectical materialism. Obviously, this endeavor is, for him, intrinsically linked to Hegel. But, at the same time and correlatively, Hegel thereby—and surprisingly—becomes the thinker who allows for a rethinking of the idea of emancipation (communism). Against all odds, by constituting a new Hegel, our Hegel has enabled a new understanding of politics by returning from Marx to Hegel, as though “sacrificing” or “letting go” one of the most important thinkers of communism and turning to the materialist heritage of idealism. The “letting go” is part of a renewal. And where else but in Hegel does our Hegel find the conceptual tools to realize what Marx has desired to achieve? By moving from our Hegel to the Hegel that he brought into life, the minimal difference between Hegel and (our)Hegel is what makes possible a new thinking of politics.

10– The thinker in question allows us, therein, to take a distance, too, from our own bloomy fantasies of emancipation—which, again, can be quite annoying. He contrasts it to a rather gloomy, or more realistic, picture of what we should expect from emancipation, liberation or even communism. Instead of believing in an idealized manner that in a future society all antagonisms would be resolved, “our Hegel” points to the inherent negativity even of such a state of society. Even communism will not be a form of organizing society devoid of jealousy, resentment, and the like. In it, “the wound of spirit leaves no scar behind,” because the process of healing produces yet another wound. While it may generate (political) resistance, resignation or disappointment, this gesture transforms fundamentally our conception of emancipation.

11– The philosophers had only interpreted the world, in various ways. Then, there was Slavoj Žižek who has changed our understanding not only of the world but also of what it means to change or interpret the world and, thus, of philosophy.

Happy birthday, tovariš!

Text by Agon Hamza and Frank Ruda

Source: http://thephilosophicalsalon.com/eleven-theses-on